Keep it Simple!

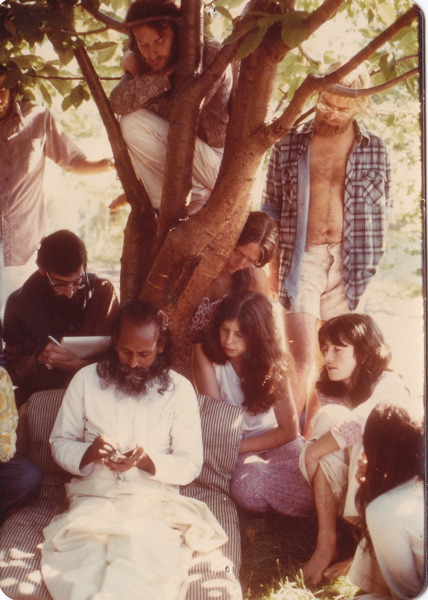

Here is Babaji’s response to a letter from one of his students:

Here is Babaji’s response to a letter from one of his students:

Simple and straight understanding is better than getting into complicated philosophies. I make it very simple for myself. That means ‘keep God’s presence in my heart and move on.’ I don’t think about life after death, what I should do for others etc. If my heart and mind are in a positive place then all actions of the mind and functions of the body are being guided by that divine power. So, why should ‘I’ think about helping, serving, doing things? ‘I’ should just go on and everything will happen by itself.

The future is unknown. When we are walking towards the unknown, a dark space, we carry a lamp. That lamp is the ego in worldly-minded people, and in spiritually-minded people that lamp is divine presence. Both are walking towards unknown dark spaces, but one is afraid and the other is fearless.

Everyone will die, it is as real as the sun will set, but humans live in a state forgetful of death. This state forgetful of death brings attachment to life. That attachment creates an individual’s world. Keep the lamp lit; walk on step by step. You can’t go astray but will merge in the light.

Babaji is exceptionally practical – this is obvious on the material plane such as his skill at building rock walls, but it is also true of his philosophical approach. Though he patiently responds to questions about astral travel, reincarnation, auras, supernatural powers and the like, his advice is always down-to-earth. “I like to keep things simple” he has often said. He also says: “Philosophy is not practicality.” Complication is necessarily of the mind, and the ego gets great satisfaction in separating, analysing, creating theories and explanations, and above all creating plans for a future with less suffering and more pleasure. These tendencies remain even after we take up spiritual practice and many years may pass before the realisation that any mental constructs are, in the end, limiting. Indeed, the truth is so simple that when the inner shift away from identification with the illusory ego of individuality takes place, the futility of the previous struggle is seen as a great cosmic joke. We see that in reality we were never really in bondage – it was our myopic way of seeing that obscured our natural freedom.

There are many simple eastern teaching stories that try to convey the illusory nature of the human struggle. One describes the plight of the prisoner who is thrown into a jail cell. The guard slams shut the heavy door and the prisoner is left to contemplate the thick stone walls and the high barred window. He is indeed in despair, but has not realized that the guard forgot to lock the door! Is he free or imprisoned? Another story is the very poor man wearing a cast off coat that, unknown to him, has a thousand dollars in a hidden pocket. Is he rich or is he poor? Perhaps the best story is that of the monkey catcher who buries a jar up to its narrow neck and puts some peanuts in it. A monkey discovers it, puts his hand in the jar, grasps a handful of nuts but then is unable to pull his hand out. He struggles hard to no avail until the monkey catcher arrives to take him away. All the monkey had to do was let go of the peanuts and remove his hand but he did not understand that simple truth. Was the monkey truly trapped?

In all these cases the bondage is not real but is caused by ignorance of the truth of the situation. In spiritual terms, that ignorance, termed avidya in Sanskrit, is at the root of all our suffering. Babaji was once asked if, aside from all the particulars of spiritual practice, he had just one simple piece of advice for spiritual seekers. He smiled and wrote: “Give up all your attachments.” He might have said: “Let go of all those peanuts!”